![]()

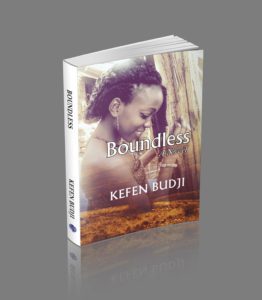

Kefen Budji – (April 2015). Boundless. Spears Media Press, 254 Pages – Available on Amazon.com

By Innocent Chia; Twitter: @innochia

In and beyond the trench lines of the battlefield of colonialism, where people were killed with bullets from guns and poisonous spearheads and bows and arrows, were unfolding parallel narratives of love and heartaches, of life and death, and of enslavement, money, wealth and power. Boundless, by Kefen Budji, is a juxtapositioning of clashing cultures, values and people that cohabit in colonial time capsule between 1910 and 1921 in Cameroon, Africa, and played out in the lives of specific characters and communities during and beyond the 243 pages. In the meantime, and as if in answer to the generational question of sexuality in Africa, the author intersperses constructs of courting, sexuality and public displays of affection in a traditional African setting, oftentimes in contrast to its Western displays. Samarah, the central character of Boundless, feels beholden to her tradition, but is left to answer the question -“does love conquer all?”

In and beyond the trench lines of the battlefield of colonialism, where people were killed with bullets from guns and poisonous spearheads and bows and arrows, were unfolding parallel narratives of love and heartaches, of life and death, and of enslavement, money, wealth and power. Boundless, by Kefen Budji, is a juxtapositioning of clashing cultures, values and people that cohabit in colonial time capsule between 1910 and 1921 in Cameroon, Africa, and played out in the lives of specific characters and communities during and beyond the 243 pages. In the meantime, and as if in answer to the generational question of sexuality in Africa, the author intersperses constructs of courting, sexuality and public displays of affection in a traditional African setting, oftentimes in contrast to its Western displays. Samarah, the central character of Boundless, feels beholden to her tradition, but is left to answer the question -“does love conquer all?”

Whether or not love conquers all is the central pillar, I would argue, around which Budji builds the walls around Samarah and leaves her grappling, alongside the readers that she takes along on the journey, on where and how to place the other foundational pillars. Would Samarah’s forebears be happy with her decision at the end, knowing what she has endured and how they were sacrificial lambs at the altar of the antagonist – colonialism? What about forgiveness, a foundational precept of the Christian education to which the father of Samarah had himself enrolled her? How much of it was she supposed to apply in her life, and when? What about the values of her parents and the culture in which she had been brought up?

Some determinative clues are dropped along the way, including the last words of Samarah’s beloved mother, Yenla, to her petrified, battered and bitter daughter. “No, my child…leave vengeance to… to the gods…” (pg 45). These words sound like they are right out of the Bible, except that in the Bible they are spoken by the Lord – “Vengeance is mine” (Deuteronomy 32:35 and Romans 12:19). What does it say that the dying words of a “heathen” is about forgiveness? Does it speak to universal human values? Whatever the case, and Christian or heathen, we eventually agree with Samarah, or not, that some things and people (Lucy) cannot be forgiven.

Like Samarah her protagonist, Budji is a little less worried about the conventional and charts her own course. While she teases with scenes of courting in pristine Africa – (pg 21-24), it remains unsettling that she does not unleash any black on black steamy foreplay and sexual intimacy. Severally, she takes us into the bedroom and pants of Mayne, the plantation heir, who is quite the ladies man, including with Lucy, the nemesis of Samarah.

It is also disappointing, I think, the flatfooted development of two important characters in the novel – Bessem and Carl. Even when Budji brings them to close proximity, she never lets on as to the possibility of any sparks between these two, not even when Carl is drunk on his matango – the native brew. We meet Bessem as a house help and she never grows out of it, nor are we ever taken into her private life as much as she shares an important role in the lives of the Samarah and Mayne.

It is instructive that Budji painstakingly provides dates and accurate historical venues, battles, and other verifiable facts. In fact, her chapters go by calendar year (1910 – 1921) and even specific months within those years. These gel together for plot plausibility and desired believability. But it does highlight, even when the Chefwa and its people are fiction central, that the centerpiece of Boundless is not the historical narrative or even historical accuracies. The centerpiece at all times is a fairytale, not particularly of Samarah. It is also arguably about the unfinished business of the assimilated and subjugated people of Southern Cameroons, and there is no place better than the last sentence of the novel to state it via Samarah’s voice – “As she raised her head to receive his kiss, she fervently wished that her country, and Bintum, would one day have their own fairytale” (pg 243).

Boundless is replete with twists and turns that knock the socks off your feet even when you think you have it all figured out. Budji more than delivers for a debut writer. She leaves the reader dreaming that hope is never lost if you only care to look hard enough around you and in places where others only dream of.