![]()

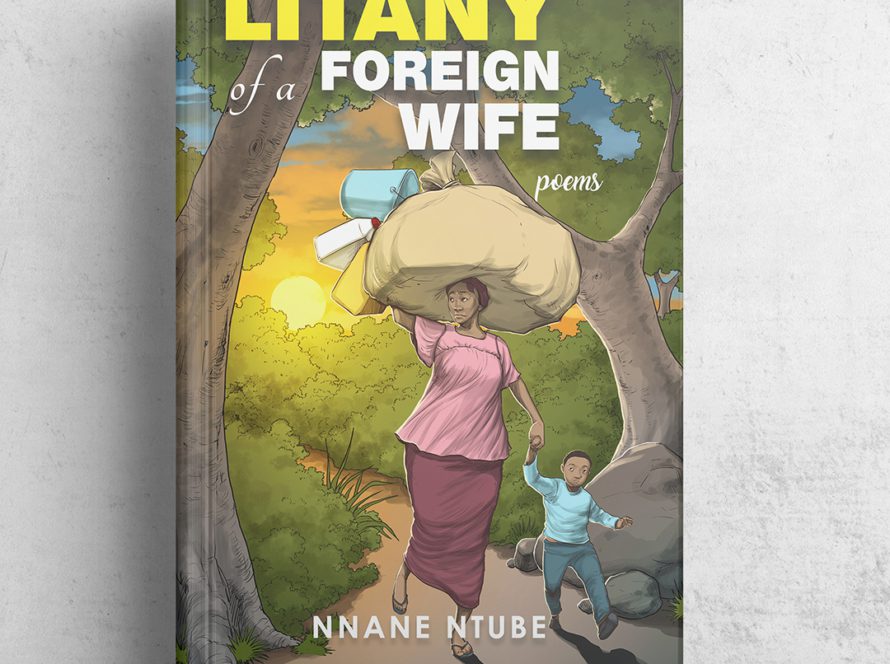

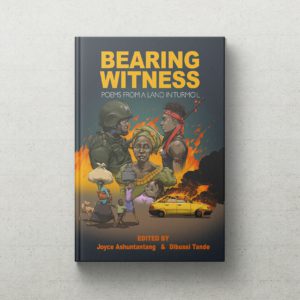

Bearing Witness: A Protest in Poetry

By Samira Edi

This compendium pulsates with rage. A rage that had been smouldering with the intensity of a welder’s blowtorch for decades, before erupting into a full-flared conflagration. It is a literary buffet of Cameroonian poets, driven by the galvanizing idea to comment on the cataclysmic events that saw a seismic change in the socio-political landscape of the two Anglophone regions. The different poets managed to capture the angst and the hopes of a people trying to piece together the fragments of their broken lives.

A smorgasbord of catastrophes cast an unsettling atmosphere over the once bustling towns and villages. Now, they’re like relics of another era, today abandoned to ghosts. It is evidenced in the empty classrooms, the unlit offices, the vacant homes, skeletons of charred and unfinished buildings, abandoned farms, the awful smells of killings, the kidnappings and the scorched carcasses of cars by the roadside.

These writers are caught between patriotism and rebellion, loyalty to the union and an unapologetic infidelity to that same coupling. On a moral as well as on an intellectual level, some decry, while others celebrate. Some lament the absence of peace, as others valorise warfare and encourage the civil disruptions. Some denounce the loss of identity, bemoan the lack of justice, are outraged by the incipient accumulation of illiteracy, as a generation of children are denied education, while the didaskaleinophobes (those who fear education) enthuse and rejoice. Some protest the unspeakable barbarity on women and the young, while others delight in them. It is reflected in the tales about the wasted lives of Anglophones, untimely dispatched into that country beyond from which no traveller returns.

“Bearing Witness,” is a veritable soufflé and a across-section of diverse opinions; a symbol that heralds the virtues and the vices of our ramshackle times.

The demise of the great Anglophone Community has not been prematurely foretold. The Anglophone Cause began as an admirable ambition before it hit a discordant note. The community got splurged with a potpourri of bad ideas and a stream of inexhaustible violence. A steady supply of mindless mayhem proclaimed its diminishment. It appears as if it was given a terminal prognosis from the start and proceeded like a knackered horse in the last throes of its existence.

By the glittering waters of the Atlantic in Victoria, to the cascading crystal-clear Falls of Menchum, from the majestic peaks of Mt. Fako, and the undulating escarpments of Mt. Oku, the land got disembowelled from within in the hands of its enemies; known and unknown, strange and familiar, global and local. Sometimes, the evil hand that wielded the knife which slit a throat in Kumba, belonged to a prodigal son of the soil. And the arsonist who burnt a family home in Mamfe turned out to be the once-friendly neighbour—a testament of entrenched betrayals and a new ethos of venom.

From Donga-Mantung to Ndian, on the alluvial plains of Ndop, the highlands of Santa or the Twin Lakes of Muanenguba, a deep groan of bitterness and pain emerged from a gorge of historic grievances, amidst the towering infernos embracing the firmaments. In the creeks of Bakassi, the staccato cracks of gunshots ricocheted across the landscape, as the angry breakers of River Manyu roiled in turmoil, not by-passing Ekiliwindi. The streets of Belo ran crimson, while in Bambili, a head got severed—but it rolled all the way to Bali and Batibo. Tiko drink Kumba drunk! The earth throbbed with a stampede of feet pounding the pavements in Buea and Bamenda, hastening away to escape the approaching terrors. The very ground moved beneath their feet like a black carpet of death as they fled to Douala, Yaoundé and Calabar.

This vortex of chaos is the background and the raw material which lends itself to the various narratives and perspectives of poets as witness. You could be forgiven for thinking that given the gravity which inspired the anthology, these writers spoke with one accord in a show of Anglophone solidarity. However, some of the contributors exude very ambivalent attitudes towards their country—expressed by the individuality of their political, moral and social positionings. Many are conflicted about the conflict—as they feel the pull of overlapping ideals, owing to the rich diversity of Anglophone ideologies. It is safe to state that most, if not all stripes and nomenclatures are represented. This poignantly shows the hybridized nature of the stakeholders from the Anglophone community. A panoply of divergence and disunity is inevitable. There’s the Southern Cameroonian, United Front, Amba, SC Bar Association, Anglophones, the Consortium, Women for Permanent Peace and Justice—WPPJ, ASCPC, SCACUF, WCC etcetera.

Like the Swiss, the discerning editors; Ashuntantang and Tande navigated a delicate balance by taking a neutral stance. Although they submitted poems which give a hint of their own political inclines, they harnessed the dynamism and the collective talents of Anglophone literati, by allowing the verbiage, the vituperations, the versifications, the pronouncements, the pontifications and the screeds from every creed.

Poets are the chroniclers of the battles of our time; hence they offer to the readers a diversity of the peoples’ minds, both as a collective and as individuals, confronting the dilemmas that have plunged their regions into a tailspin. Whether they’re for or against the struggle, the contributors cast a wistful gaze or a side-eye of despair, at the legacy of teachery currently reverberating across their regions. They echo the stories of the voiceless, and vocalise the unceasing fiery horrors that have engulfed the land. They lament the plight of the disenfranchised refugees, now eking out an existence in foreign lands, under conditions to which they’re unaccustomed. While their political leanings may vary, every poet agrees that something terrible has befallen a land which was once on the verge of Nirvana.

Margaret Awanto’s poem, “Why Are You Leaving Home?” is a nostalgic sob over lost memories. It is also echoed by the poet Beatrice Fri Bime in “Confusion Everywhere.” These two poets grudgingly grieve and grapple with the new eccentricity, in a place they no longer recognize as home. These are the same sentiments reflected by Douglas Achingale in his entry titled, “Strange Land.” There’s been a misstep in the wrong direction; with the incalculable loss of everything that once represented the essential elements of normalcy. Home has turned into “…a tavern of drunk raucous men, searching for power in all the wrong places…” This is a resounding rejection of an exile in flight, who is unable to fathom questions about her previous home. As she steps into a new world, any vestiges of the familiar; like the smell of suya, is a painful reminder of a home that’s no longer there. Hers is a powerful political voice representing those who unequivocally denounce the atrocities in her homeland. She ends her poem with a brusque dismissal, “Do not ask me about home,” just like Bime’s complaint, “I don’t like what I see.”

The established poet Victor Epie ‘Ngome, feels the pinch of a patriot betrayed. With a particularly provocative entry titled, “Faded Icon,” this veteran writer nails his colours firmly to the mast of a revolutionary:

“I’ll burn no flag

For ‘tis but a fabric and unworthy

Of the raging fiery fury

Within my heart and soul.”

His eloquently sneering tone affirms his political position. He doesn’t achieve congruence with the dichotomies espoused by the likes of Awanto or Edi. His metonymic disrespect for the “Flag,” reflects his feelings of contempt for what’s happening. He calls that once iconic piece of fabric a “rag;” which is a downgrade of the country whose stature is diminished in his eyes. However, rather than burn it, he’ll just spurn it.

Epie’Ngome follows up his denunciation with another poem titled, “The Village Bully;” which is a derogatory metaphor for the government he condemns. He carries on in the same vein by listing its egregious atrocities. His final entry segues into a revolutionary cry to “Wake the Nation,” a rallying roar to stir the consciousness of the people in every corner of our Triangle in organised dissent, to rise from their “slavish slumber,” by casting off their comfort blankets and doing something.

Some poets leap from verse to prose—fixated on giving harrowing accounts of the peoples’ experiences. Many showcase a catalogue of crimes, occasionally written in Pidgin English to convey a realistic scenario, before swapping to standard English. Lucidly eloquent, they capture in forensic details the raining turbulence on Ground Zero.

Dibussi Tande’s, “When the Phone Rings,” reads like the tapestry of News in Brief. He provides a horrified glimpse of the unfolding bleakness, a style which Patricia Nkweteyim brilliantly emulates in, “Wahala Don Come.” Seemingly, innocent people engaged in their daily grind are caught in ugly situations not of their making. Written in fine Cameroon Pidgin, Nkweteyim employs onomatopoeia, (ratatatat, boom boom,) to evoke a sense of the terrifying soundscape in which the victims get caught in a catalogue of crimes. Tande speaks for, and epitomizes the plight of the anxious Cameroonian in the diasporas, who must brace himself for the inevitable bad news from home every time the phone rings. Conceived in a manner that lacks all restraint, no news is good from Ground Zero. No wonder, this poet follows up the tragic scenario with two bleak tributes titled, “Nightmare,” and “Broken Spirits;” titles which are self-explanatory.

Nnane Ntube’s elegiac poems “Gone,” and “Ghost Town,” drip effortlessly with the enduring melancholy that has enveloped the land. Achingale elicits the same sentiments in his morbidly titled piece, “And the Baby Died.” Both writers paint a gruesome picture of the nightmarish activities that lead to the deaths of the innocent, just like Maa Nka’a’s two very emotive entries about dreadful human experiences, “One Grave, Thirteen Bodies,” and “The Blood Festival.”

Ultimately, our fairgrounds have turned to killing fields. Butchery reigns, which another poet, John Ngong Kum Ngong evokes in graphic details in, “I Saw Them.” Focho Gladys will take this to another level of dolefulness in a hard-hitting entry. She writes movingly about the spine-tingling wails of a mother in dismay, who mourns the death of her child, “Rigobert! Rigobert!” For Rigobert is no more.

Lloney Monono takes umbrage with “the union.” He frames his verse, the “Autumn Dance,” in the form of an intricately woven saga of a loveless marriage which began with a lady being deceitfully lured onto the dancefloor. To give it its proper historical context, it’s a metaphor for the unification between Southern Kamerun and La Republique du Cameroun. This unhappy couple is engaged in a macabre dance, which is a true dictator’s envy. The lady plays out the entirety of their abusive relationship in her head space, citing a wide range of irreconcilable differences why she wants out of this mismatched wedlock. But oblivious to her protestations, the tone-deaf husband carries on. This is a recurring theme, visited by others like Dibussi Tande, in his elegantly-written poem in Pidgin English, “NoSo Nonsense,” which challenges the thorny issues of bi-nationalism and bilingualism head-on. Monono’s words ripple delightfully off the page as an epic in storytelling. The marriage has deteriorated to a state of perversion, seen via this tango with a monster. The man forcefully in charge, takes his reluctant wife through her paces. Her insistence to disengage from something which is no longer desirable goes unheeded—compelling her to demand, “Who do you think you are, Mr…?” Big Stuff, perhaps? She’s like an ensnared fly, trapped in her husband’s web. He remains impervious to her complaints and keeps up a dictatorial refrain, “You’re mine, mine, mine,” to signify her eternal enslavement.

I was intrigued by Nol Alembong’s unabashed submission titled, “Wartime Ladies.” Here’s a writer who’ll outburn Robert Burns and make that Tartan bard to blush like a shrinking violet. His unconventional style departs from the norm as his beautiful poem is interlaced with Pidgin English, French, English, Franglais and Ewondo; which symbolizes Cameroon’s multicultural linguistic heritage. Crafted in a vernacular that isn’t easily discernible to the uninitiated ear, his poem is a study in colloquialism as he works himself into a sensual rage. He writes about the sacrilegious peccadilloes of some easy chicks who display very titillating behaviours.

In a colourful lingo of his own devise, Alembong takes on this kaleidoscope of promiscuous entities who came out to play when the war broke out—a bevy of naughty vamps each with her agenda. They wave an assortment of flags; nkengs, palm fronds and handkerchiefs, like calling-cards, as some engage in futile prayers for the “Ambas,” in an attempt to persuade or dissuade this hardy bunch of warriors. Amongst the prayerfully impious lot, are the over-sexualized saucy minxes who flaunt their bodies for money. Nubile ingenues whose perky breasts seem to suggest, “thou shalt commit adultery,” seduce men to satisfy their lusts. The fast-talkers who swig champagne try to serenade those home-made hooligans with temptations to engage in improbable love affairs when, “…the sky was red with flying bullets.”

Meanwhile, like the infamous voyeur, Tom, the poet peeps from his ivory tower while he secretly vilifies their pursuits. He asks, “love fit make mami-fowl forget say hawk dey for bush?” His poem is a sad reflection of the reality of what some women became during the war—facile Jezebels casting seductive glances at opportunistic, predatory men. He cements his credentials as a social critic who condemns the pyrrhic nature of war, with another poem about child soldiers titled, “Pikin Soldier Dem.” Children are the casualties of the bad decisions made by adults because, “pikin soldier dem die pass grass…”

Alembom’s “Wartime Ladies,” is reminiscent of the staged intervention of Ashuntantang’s dramatized poetry, “A Village in Seven Vignettes,” only as far as style is concerned, because they both stretch the limits of their poetic licences by juxtaposing and interspersing their verses with commentary about the unfolding tragedies. Ashuntantang insets herself into the teeth of the action, performance-style, like a guru of gonzo journalism, to challenge the dreadful absurdity before her. She confronts the encroaching violence sweeping the land with words directed at the readers, to add context, clarification and advice.

From the pedestrian to the elevated! JK Bannavti is a poet who seems to bestride the political demographics of two opposing factions, by taking the reader on a guilt trip. He appears non-committal as he tries to persuade his interlocutors one way or the other to establish the guilt or innocence of his characters, showcasing both sides in their worst light. Firstly, in his poem “Carnage in Tadu,” he describes a blizzard of evil committed by the soldiers, whom he calls the “Vibaiy.” They have the cruel temerity to empty their muskets with callous indifference into the bodies of innocent villagers; amongst whom is an old, frail, weak, and sick grandpa, of whom they made an example. They spare nobody as they pillage the villages, ransacking every nook, trying to smoke out “amba boys” or the “Won-Nsai.” Meanwhile, in another poem, “My Sister’s Son,” it is the “Won-Nsai;” sons of the soil, who’re the villainous fiends. They invade the hut of a grieving widow, pulls out her only boy, slams him against the wall and puts a bullet through his head—no explanations given. This poet tells the tragic tales of a people caught between the crosshairs of two murderous villains; co-conspirators of terror.

Samuel Tabi Tanyi-Mbianyor is a poet who articulates the tangled wreckage of a land bathed in turmoil. His haunting narrative, “After She Spits a Mouthful of Stars,” pays homage to the women caught in the conflict. It is a stunning retelling of their losses in which they’ve suffered untold atrocities in the hands of miscreants. Tanyi-Mbianyor elevates the lot of these hapless female victims into the realm of cosmic mystics. He extolls their virtues, for like phoenixes they’re transfigured to rise above their sufferings. Despite their miserable deaths, they’re revived to sparkle like stars, and no mortal hand possesses any devices to harm them any longer.

His other poem titled “Yet We Arrive,” would fit with Beckett’s Theatre of the Absurd. He paints a breathtakingly dystopian image that illuminates the plight of a people in flight, determined to forge ahead on a quest for their own nirvanas. Their journey is not without incidents but they overcome great obstacles; occasionally stumbling against the ramparts of a harsh and unforgiving terrain. They’re stung by killer hornets, which sees some members die along the way, while others lose limbs in the process. They wade through thick filth and foliage in the forests, thread on hot sands in deserts, all in an attempt to capture the, “sounds of a distant hope…to a home which is not home.”

Tanyi-Mbianyor’s last entry titled, “A Thousand Ghosts Have Come to Town,” is a gothic that contiguously mirrors the carnage of which he previously spoke, about a people disgorged from their lands. He shines a light on the towns, now inhabited by marching zombies who introduced their alien cultures; like violence or a rape-fest. Their fellow travellers; the bearded dragons course through the deserted market stalls, like the new land owners who’ve managed to turf out the legitimate inhabitants. Like Epie’Ngome, Tanyi-Mbianyor says the people must brace themselves and resist for, “we cannot whisper our wishes underneath our breaths anymore,” as a gesture of collective catharsis, to open a gateway to healing and a new destiny.

Lily Atanga asks a solemn rhetorical question, “Where Has it All Gone (to)?” She laments the absence of normalcy, a reference to a breakdown of civilisation during these perilous times. Her question hangs in the air unanswered, as long as the conflict persists. Her second entry is about a wandering minstrel, trudging aimlessly through the forest, starved of all but the bitter memories stored in the canyons of her mind, which she replays along the way. As she embarks on her solitary sojourn, she breaks out in song; “Songs of Hope;” her only companion. Like Ekpe Iyang’s poem, “Peace, Peace, Peace,” she would hope this state of desolation was just one big bad dream from which she must awake.

One of the most stylishly-crafted poems in the collection is written by Rose Ndengue who embodies the citizen with a fealty to the country, and who doesn’t condone the general odium, one way or another. In “Trilogie Poet[i]que: Rebrand Cameroon,” she writes in both French and English, a potent reminder that begs the question: what percentage of a Cameroonian’s linguistic circumstance identifies them as Anglophone or Francophone? It makes a compelling case for those wrestling with their dual, if not multiple identities. Her position may appear simplistic, but she’s not being facetious when she argues that the country has a problem, but the solution is not a break up, but a rebrand.

In my irreverent submission, “The Master Craftsman,” I’ve ventured onto the hallowed grounds where angels feared to tread. It’s an audacious poem that brings a new resonance about a cause that’s become a miasma of unmitigated disaster and a profoundly dehumanising experience to the affected. It is written with an amplitude of irony and nuanced with copious lashings of suppressed fury. I give a subtle nod to Robert Louis Stevenson’s eponymously flawed character with a double personality disorder; Dr. Jekyll, who straddles both sides of morality. Like night follows day, the “genius,” about whom the poem is written turns out to portray less of the good Dr. Jekyll and more of the villainous Mr. Hyde. It is a fitting representation of a people experiencing reverse metamorphosis in the wake of the crippling conflict. It exposes a dizzying degree of our own Taliban-like/Boko Haram-like attributes. I give a big woof to the parasitic leeches who got above themselves and hijacked the revolution. Instead of progress, we regressed like butterflies mutating into ugly caterpillars. The main character is a self-destructive arsonist.

The poem is a scathing denunciation of the hypocrisy of those who claim to be the people’s liberators, but turned out to be their oppressors. Like Ngasa Wise Nzike’s defiant entry titled, “Amba,” (nchang-shoes-wearing oddities,) a bunch of emboldened nobodies, once abandoned to obscurity, crawled out to impose themselves as the grandees of the revolution, while sowing bedlam and terror.

Laced with the courage of “Odeshi,” self-proclaimed “commanders” commit unspeakable atrocities because they possess the profane weaponry to keep the people meek, lowly and scared. Helped by Dutch courage, sniffed in white powder or Tramadol, these newly-empowered, self-appointed leaders mirror the medieval barbarity of regular soldiers, both in cruelty and ferocity. Instead of using their “genius” for good, their callous actions have caused the revolution to lose its moral backbone, the goodwill of the international community and the loyalty of the people whose lives came to a standstill. The proof of the existence of a monster is the presence of its victims.

If the number of the maimed and the murdered count for something, there’re gargantuan monsters in the Anglophone community, red in tooth and claw. They’ve used their expertise to self-destruct—a situation comparable to what Monique Kwachou describes in, “Miscarriage of Justice.” It is the perplexing story of a brilliant person, in the grip of his delusions, who snatches defeat from the jaws of victory. Once filled with promise, he sets about systemically dismantling his home. He’s an opportunist predator and a wolf-in-sheep-clothing, motivated by greed. “He is seduced by something more—the gold.”

It would be unfortunate to comment on the artistic merits of the poems. Some are written in Pidgin English, a language long considered the lingua franca of the streets, but which happens to be the most appropriate for poetic delivery in some cases. Many were crafted by amateurs without any regard for the rigours of the art form—but whose passion comes out palpably, in ways that express the anxieties which inspired them. They write emotionally on a patriotic whim, like the living witnesses caught in the crosshairs of an evolutionary drama. Many have the impetuosity of youth, expressing themselves with the passions of patriots, fervently lamenting and counting their losses. It is a cathartic gateway to healing.

There’s a load of scepticism in the question, what now? What happens now, that the land has been decimated and the people chased into the woods? Christmas Ebini writes a sorrowful lament titled, “Voices in Exile,” “Hear my cry and remember it, for I do not only cry for me…Now I do really feel the pain of the exile—calling off the bluff of the cowards and fully taking our destiny into our hands.”

That may be, but we heeded the call of the wild to rapturous acclaim once, sailed into a man-made mess and arguing like opposing counsels in court. We crossed the Rubicon to scale the heights of folly, creating what Yusinyu Titus Nsami calls, “Monsters to stop other monsters.” We’ve dipped our swords and soaked our streets with our own blood because, “monsters cannot protect, monsters only oppress,” like Nsami says. We’ve even immortalised our complaints in a poetic monument titled, “Bearing Witness.” So far, we’ve reached a stalemate.

Whether you favour the F word; “Federalism” or the S word, “Secession,” it’s time for a rethink. Let’s return to our traditional roots with cowries, breaking kola-nuts and pouring libation palm wine to the ancestors to invoke peace. “Peace, where are you? You are welcome into my hut,” intones Emerencia Bih. I couldn’t agree more. Insanity means building castles in one’s mind and living in it. It is time to stop the delusions. We must move away from of the myths of unrealistic expectations in the stratosphere. Poetry should make us think and this volume provides plenty of fodder for that. Seize the moment, says I.