![]()

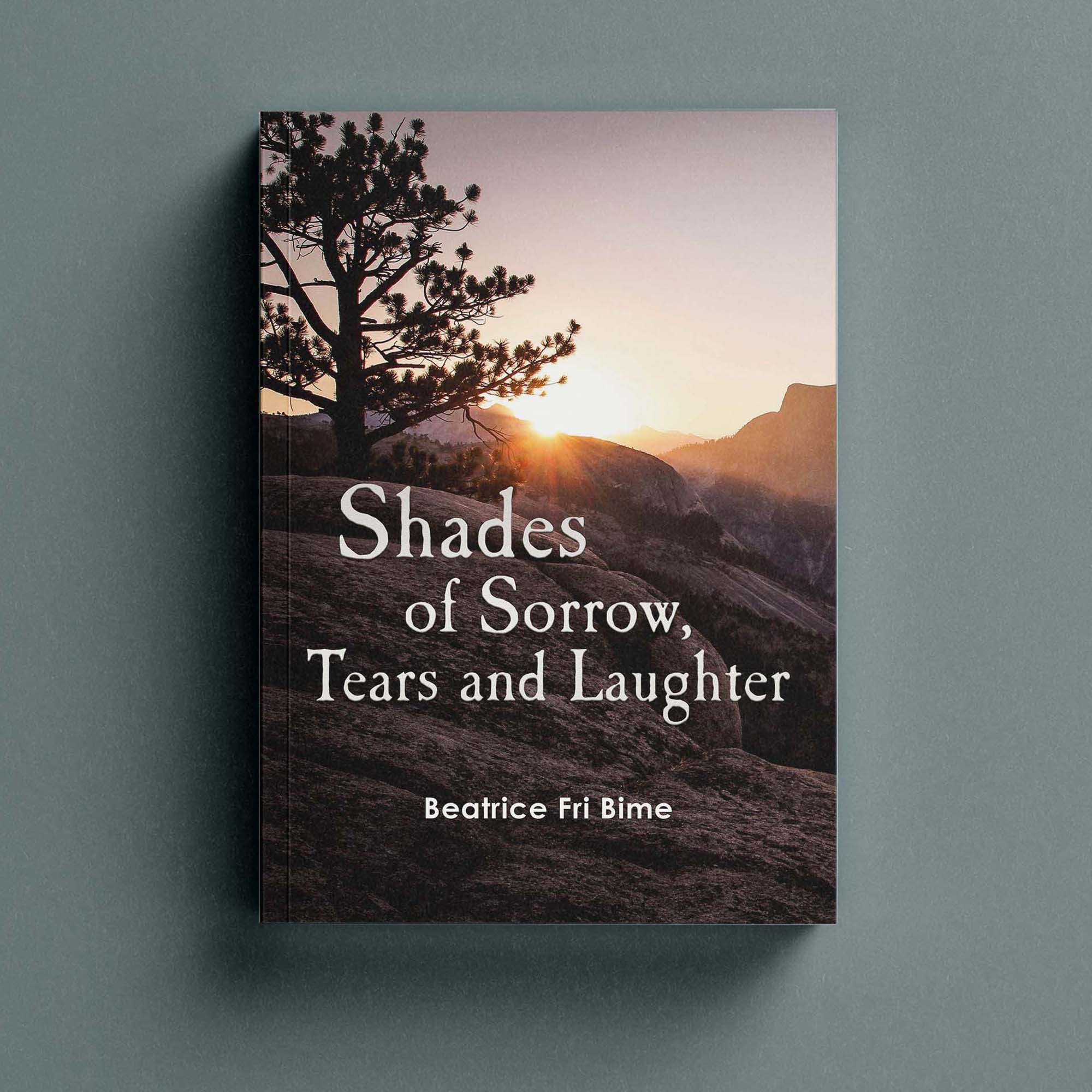

Interrogating the Shades of Life: A Review of Beatrice Fri Bime’s Shades of Sorrow, Tears and Laughter

By Professor Eunice NGONGKUM,

University of Yaoundé 1, Cameroon

The foremost English critic, Matthew Arnold, once observed that “poetry is, at bottom, a criticism of life; that the greatness of a poet lies in his (her) powerful and beautiful application of ideas to life; to the question: How do we live?” Arnold here simply meant that poetry should be relevant to the lives of people and shouldn’t be far-fetched as to have no direct contact with humankind. This observation aptly applies to Beatrice Fri Bime’s Shades of Sorrow, Tears and Laughter; a poetic tapestry of 66 pieces of varying length rendered in 12 shades of unequal length. Here, Fri Bime’s appealing lyricism, her uniquely simple but witty voice, invites an engagement with issues that pertain to life; to all of life, in her immediate vicinity and beyond.

In Part One, entitled ‘Poems of Reminiscence’, memory is positioned as a source, not only of poetic inspiration but of understanding behavioral patterns. Whether it be moments to be cherished, certain social habits to be deplored or lost friendships to be regretted, the twelve poems of this section pulsate with the weight of memory; with what was, what could have been, or what has become of these lived experiences. Anaphoric references and imagery serve to heighten the tone of regret in these poems.

Part Two has as title, ‘Poems of Optimism.’ As a contrast to the first part, the poems underscore the personae’s hope for harmony and integrity in human relationships. In “Still I Stand”, the tenacity to withstand uncalled for attacks is celebrated. This tenacity, the reader is made to understand is undergird by a firm faith in God who sustains the speaker in the storms of life. This is the same God who helps the speaker find his/her best self; a best self, unique in its essence and incomparable to none, as we find in “Searching for My Best Self.” The lyrical quality in this section is again sustained by repetition, biblical imagery, and witty aphorisms. Part three’s two poems are negritudinist in perspective. They celebrate Africanness; a celebration that transcends the obvious color/ racial paradigms to include natural landscapes, social relationships, the laughter, the song; indeed, all the basic rhythms that govern communal life on the continent. In this way, Fri Bime marries some of the twin aspects of negritude poetry, namely the negritude of celebration and that of affirmation.

In the fourth section entitled ‘Poems of Lamentation’, seven vignettes lament our contemporary polity “the land of milk and honey”, bedeviled by conflict, war, corruption, and pandemics. The realistic overtones in this section reinforce the pain of loss, the pain of witnessing the double and sometimes triple tragedy that befalls the casualties of war far away from their homes. Many, run away from war and conflict only to face the war of life in the city, eventually succumbing to either the bullets of neglect, callousness, and outright sadism, or to the Covid-19 pandemic. Poems like “Nameless”, “Death”, and “Double Pain” are built on this kind of foundation.

Part Five (known as Poems of Existentialism), is made up of six poems that interrogate the ‘Whys and Wherefores’ of life especially as these occur at the individual and relational levels. In Part six, nine poems satirize reckless living, American politics in the age of Trump, ingratitude, and power politics. In this section, irony is aptly employed to underline the ephemerality of life, the hypocrisy of the human heart and the nouveau rich syndrome. This part is immediately countered by the next one dedicated to love. Love is portrayed in its multifaceted ethos, namely, as an inner treasure that must be sought for in the other. It is also shown a touch of paradise, even more so when it ends up in a marriage celebration that is lost to temporalities, even so, because of the sheer ‘pleasure and joy’ holding the crowd spellbound as we find in “A Touch of Paradise” and “Marriage.” On the flipside, poems such as “Not Enough”, and “Drained”, reveal that love is something that must be nurtured and sustained, failing which it can be lost or simply die.

Part Eight is entitled “Poems of Conscientization”. The three poems in this section conscientize readers on the ill effects of war, treachery, and bad governance. Through rhetoric and the questioning voice of the child in “Tinted Glasses”, the section lays bare the incongruities of war and the politics of greed that fuel it. In the section, ‘Poems of Nature’, physical nature (butterflies) and built nature (roads) are employed to discuss the qualities of fickleness and human destruction of the natural environment to construct roads that end up destroying human life. Whereas one would have thought non-human nature would be presented in its own right in the poems, it continues to serve as a vehicle for the discussion of human emotions. This is, of course, consistent with the poet’s vocation of attending to human life as we observed in preceding paragraphs. ‘Poems of Oppression’ constitute part ten of the collection. Here, seven poems x-ray varying forms of oppression such as police brutality and excesses, in “I Don’t Understand”; war and conflict in contexts gone awry as we find in “Beyond Madness” and “No Place to Hide.”

Parts Eleven and Twelve are devoted to the emotion of gratitude and other diverse issues. Here, being thankful in everything, ‘For all the yesterdays/for all the tomorrows” is the watchword, even as one responds to calamity, loneliness, and death.

The late Indian-American poet, Meena Alexander, observed that the “task of poetry is to reconcile us to a violent and unjust world—not to accept it at face value or to assent to things that are wrong, but to reconcile one in a larger sense, to return us in love…to the scope of our mortal lives.” Beatrice Fri Bime’s maiden collection of poetry, in my estimation, adequately and boldly performs this task. Through a free verse rendition rooted in social realism, devolving from a traditional view of the artist in Africa, and sustained by rhythmic and rhyme patterns reinforced by anaphoric references, repetitions, imagery, rhetorical questions, as well as biblical, historical, and other allusions, the poet invites the reader into her poetic universe to confront an essentially violent and unjust world but one that can be rescued by love, warmth in human relationships, and above all, a firm trust in God, “without whom we are nothing” and for “whom the impossible becomes possible”, as the poem, “Stuck” underlines. Fri Bime’s poetic voice is urgent, and one that must be heeded if we must make sense of our contemporary world.